In the eyes of technology: The historical, philosophical & cultural dimensions of biometric identity verification

by Sasha Shilina, PhD

This research embarks on a journey through the epochs of human history and thought, unraveling the historical, philosophical, and cultural threads that have woven the fabric of identity verification over time. From ancient philosophical wisdom to the intricacies of modern biometrics, it seeks to illuminate the evolving nature of identity in an increasingly digital world, all while considering the ethical and cultural implications that this odyssey entails. As we traverse this intellectual landscape, we uncover connections between our past and the pixels of our seemingly Sci-Fi biometrically-filled future.

* It is important to note that philosophy primarily deals with metaphysical, ontological, and epistemological questions, while biometrics is a technological phenomenon. Many philosophical concepts and cultural theories analyzed in this paper have been simplified while linked with biometric concepts. Furthermore, the majority of philosophers mentioned in this paper do not explicitly discuss biometrics in their works, and any connection between their philosophy and biometrics should be considered as an interpretive exercise.

Table of Content

Introduction

Part I. Identity: Mind and body

- Three approaches to identity

- Philosophical perspectives on identity

- Foundations of identity

Part II. Technological dimensions of biometrics

- Biometric modalities: The canvas of identity

- Touch meets tech: Navigating the frontiers of biometric building blocks

Part III. Biometrics: Historical evolution

- Roots of biometrics

- Ancient era

- Renaissance and the emergence of signatures

- Early identity verification

- The anthropometric era: Bertillon and precise measurements

- Fingerprinting: Galton and the beginnings of modern biometrics

- World War II and biometrics

- Biometrics in the digital age

- Computerization of biometrics

- Standardization and global acceptance

Part IV. Biometrics: The philosophical landscape

- Philosophical underpinnings of biometrics

- Critique of biometric ideology: Beyond the surface of security

Part V. Biometrics: Cultural dimensions

- Biometrics x Culture

- Portrayal in science fiction (Sci-Fi) and popular culture

Part VI. Public perception of biometrics

- Aspects influencing the perception of biometrics

- General trends and considerations

Part VII. Alternative frameworks for biometric identity

- Embracing biometrics for empowerment

- De-identification and anonymization: Balancing utility with privacy in the age of biometrics

- Participatory design and ethical frameworks: Shifting power and shaping responsible biometrics

Discussion

Conclusion

References

Introduction

‘Existence is identity, consciousness is identification.’

– Ayn Rand

Martin Heidegger, with keen insight, observed that every technology transcends mere neutrality. Our values, desires, and biases are a canvas for it (Heidegger, 1954). As biometrics — the measurement and analysis of unique biological features and physical characteristics that can be used to identify individuals — becomes increasingly integrated into our daily lives — from unlocking smartphones to securing borders — it is essential to delve into its historical roots, philosophical underpinnings, and cultural implications to comprehensively grasp the multifaceted nature of this field.

This research aims to provide a thorough exploration of identity verification and biometrics, unraveling its historical trajectory, dissecting the philosophical debates they engender, and examining their cultural references and impacts.

While conceptualizing the identity phenomenon and tracing the history of biometrics, we can discern the intricate interplay between technological advancements and the societal contexts that shape them. Furthermore, this examination will extend into the realm of philosophy, probing the ethical considerations, identity dynamics, and existential implications posed by the integration of biometrics into the fabric of our existence. We will explore how biometrics, as both a technological and cultural phenomenon, influences societal norms, practices, and public perception. Lastly, we will summarize general trends, provide statistics, and describe alternative frameworks for biometric identity.

Ultimately, we believe that understanding the historical, philosophical, and cultural dimensions of identity verification is not merely an academic exercise but a crucial endeavor in navigating the ethical, legal, and social implications of its pervasive use. As biometrics continues to advance, reaching into new domains and raising profound questions about privacy, autonomy, and societal values, a comprehensive exploration becomes imperative. This research endeavors to contribute to the ongoing discourse surrounding biometrics, offering insights that inform both policymakers and the general public about the complexities and nuances inherent in this rapidly evolving field.

Part I. Identity: Mind and body

‘One of the most wonderful things in nature is a glance of the eye; it transcends speech; it is the bodily symbol of identity.’

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

Who are we? Beyond mere names and appearances, what threads weave the tapestry of self? This enduring question has echoed through the halls of philosophy since the dawn of thought, captivating minds from Socrates to Sartre. In this section, we embark on a voyage of inquiry, dissecting the concept of identity through the lenses of various philosophical schools and thinkers.

Three approaches to identity

Personal identity stands as a complex matter (Hirsch, 1992; Lövheim & Lundmark, 2021) that traverses various disciplines within the history of thought, spanning from the philosophy of mind and metaphysics to epistemology, ethics, biology, and political theory. It’s not a singular problem but rather a category of philosophical inquiries that surfaces whenever we delve into questions regarding what fundamentally defines an individual.

General approaches to personal identity usually are broadly categorized into three groups (Dunne, 2022): physical, physiological, and skeptical.

- The first category is what may be termed the ‘Physical’ approach, which posits that human fundamental essence resides in something physical. Within this neurobiological framework, the research explores the biological basis of identity by investigating brain structures and functions associated with self-awareness, consciousness, and personal experiences. Advances in brain imaging technologies, such as fMRI and EEG, enable scientists to map neural activity corresponding to various aspects of identity, contributing empirical insights to philosophical and psychological discussions.

Furthermore, the field of behavioral genetics explores the role of genetics in shaping personality traits and, by extension, aspects of identity (Van der Ploeg I, 2007). Hormonal fluctuations throughout the lifespan may also contribute to shifts in self-perception, affecting one’s identity over time.

2. The ‘Psychological’ approach is another perspective on personal identity positioning that our fundamental essence is not rooted in any physical organ or organism but resides in something psychological. According to this viewpoint, a person could be conceptualized, as David Hume suggested, as a series of perceptions or impressions (Biro, 1976; Pears, 1975; Langer, 1997; Rosenberg, 2000). Alternatively, people could be understood as successive psychological connections. The distinguishing factor lies in the idea that certain types of mental states form relations that endure over time, with memory playing a crucial role. The notion that our fundamental identity hinges on such psychological connections is intuitively compelling. If an individual were to experience a memory wipe or have their memories replaced entirely, it becomes conceivable to question whether the resulting person is the same as the one existing before the alteration of their memory.

Identity formation is also a central theme in developmental psychology, particularly in the work of Erik Erikson. His theory of psychosocial development emphasizes the critical role of identity crises at different life stages (Erikson, 1967; Orenstein & Lewis, 2022).

Cognitive psychologists contribute by investigating the cognitive processes underlying identity. Memory, perception, and self-concept play pivotal roles in shaping how individuals perceive and define themselves. Cognitive theories align with philosophers like John Locke, who tied personal identity to memory (Locke, 1690; Balibar, 2013; Stokes, 2008).

Psychodynamic theories, such as those rooted in psychoanalysis, explore the narrative construction of identity. From Freud to contemporary psychoanalysts, the emphasis on personal narratives and the unconscious adds depth to the philosophical concept of narrative identity (Freud, 1923; Meissner, 1970). These perspectives highlight the interplay between conscious and unconscious processes in shaping one’s life story.

3. A third ‘Skeptical’ perspective on personal identity challenges the very nature of the problems associated with personal identity or expresses skepticism about our capacity to accurately address them. This approach suggests that there may be no definitive answers to questions about personal identity, or that such questions are inherently flawed in probing into our mental lives. Some argue that whatever response we provide to these questions may not be of real significance.

Broadly, there are three types of skeptical approaches. The first contends that we are fundamentally nothing at all, devoid of a core existence or ultimate truth about our being. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus notably advocates for this perspective (Wittgenstein, 1921). The second asserts that the question itself lacks a meaningful answer, as it delves too much into the concepts by which we understand ourselves rather than the origins of our mental lives, suggesting that the natural sciences are better suited to address such inquiries. The third type posits that our fundamental nature has minimal impact on how we perceive the world or approach morality.

On top of that, some skeptics draw parallels between their perspective and certain Eastern philosophical traditions, particularly in schools of thought such as Buddhism and Taoism (Ho, 1995). These traditions often emphasize the impermanence of the self and the illusory nature of a fixed identity.

Philosophical perspectives on identity

In philosophy, “identity” functions as a predicate, differentiating one object from another (Casiraghi, 2018; Glover, 1988; Sollberger, 2013; Shoemaker, 2003). Plato and Aristotle made key distinctions, with Aristotle emphasizing numeric equivalence and uniqueness. The problem of identity evolved into a substance problem in defining the principle of individuation.

Researchers distinguish quantitative identity, qualitative identity, and identity as self-sameness (Sollberger, 2013), with a focus on the dynamic process of individual self-conception and coherence over time.

- Quantitative identity, rooted in the Greek term “atomon,” initially signified indivisibility. However, the philosophical discourse focused on the ineffability and unknowability of individuals. Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz attempted to singularize individuals through a complete enumeration of their qualities (Mondadori, 1975). Immanuel Kant, in contrast, argued that individuals couldn’t be specified through a concept of substance (Kitcher, 1982; Rosenberg, 2000; Barber & Gracia, 1994). Instead, identity, distinct from existence, became an epistemological term tied to consciousness. The transcendental ego, according to Kant, represented a unified and unique whole in different perceptions. The issue arises when individuals are identified based on spatiotemporal localization, making it challenging to recognize them as the same over time. John Locke linked the human self to memory, stating that a person is the same if able to remember previous states of consciousness (Locke, 1690; Curley, 1982; Stokes, 2008; Balibar, 2013).

Henri Tajfel’s Social Identity Theory posits that people categorize themselves and others into social groups, influencing their social identity (Tajfel, 2010). This psychological perspective enhances qualitative aspects of identity discussed in philosophy, illustrating how roles, ideals, values, and experiences are not only individual but also deeply intertwined with societal contexts.

- Qualitative identity shifts the focus from numeric-quantitative identification to conceptual or substantial attributes. Social science often interprets identity qualitatively, classifying individuals by roles, ideals, values, habits, and experiences.

- Identity as self-sameness delves into an individual’s capacity for coherence, continuity, and integration. It is not a fixed result but a dynamic process of continual self-consciousness. This narrative self or narrative identity emphasizes continuity over time and under different conditions.

Philosophers like Anthony Giddens and Judith Butler thought that identity is not a fixed essence but a dynamic product of social interactions and cultural narratives (Salih, 2002). People navigate shifting roles, expectations, and relationships, weaving stories of themselves within broader societal fabrics.

Attempts to define qualitative identity with criteria for personhood find limitations, especially when approached solely from a third-person perspective. The first-person perspective and narrative storytelling become crucial in understanding personal identity.

Foundations of identity

Traversing the ideas from Plato to Kant

Philosophers have explored the intricate concept of identity, each contributing distinct perspectives that shape our understanding of the self.

Plato, a key figure in ancient Greek philosophy, introduced the concept of Ideal Forms in his works “Republic” and “Phaedo.” His allegory of the cave symbolizes the transient nature of empirical reality, suggesting that true essence lies in the metaphysical realm of Ideal Forms. Plato’s exploration emphasizes the pursuit of unchanging, universal truths that define the self, inviting us to discover our authentic identity beyond fleeting experiences (Gerson, 2004; Mates, 1979). Aristotle, a pupil of Plato, took a different route by grounding identity in the empirical world. Departing from metaphysical musings, Aristotle viewed the self as a unique amalgamation of particulars, emphasizing individuality shaped by experiences and interactions in the tangible world. His botanical analogy likens the self to a diverse garden, where each element contributes to the richness of the whole (Barnes, 1977; Bowin, 2008).

A herald of the modern era — René Descartes — introduced the famous “Cogito, ergo sum” or “I think, therefore I am.” In this philosophical realm, the Cartesian self becomes an indomitable point of reference amid skepticism, positioning the thinking self as the foundation of knowledge. Descartes’ emphasis on introspection and doubt marks a new era of self-awareness, urging a profound exploration into the inner sanctums of thought (Almog, 2005; Barber & Gracia, 1994).

The author of Monadologie, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz addressed the problem of identity through the principle of individuation, asserting that no two distinct things precisely resemble each other. This principle, encapsulated in a mathematical law, prevents the merging of entities and preserves their distinct identities. Leibniz’s contribution revolves around articulating how individual entities maintain uniqueness in the philosophical landscape (Mondadori, 1975).

David Hume challenged conventional notions of a continuous, unchanging self with his bundle theory, later developed by Derek Parfit. He portrayed the self as a dynamic collage of perceptions and sensations, emphasizing the transient nature of experiences. Hume’s philosophy prompts us to see identity as a constantly evolving composition shaped by the ceaseless flow of lived experiences (Biro, 1976; Davey, 1987; Pears, 1975; Langer, 1997).

Immanuel Kant, an Enlightenment luminary, introduced the concept of the transcendental ego — a self that actively shapes reality. Kant’s philosophy elevates the self to the role of an autonomous agent, orchestrating sensory perceptions into a harmonious composition of reality. In Kant’s construct, the self is not a passive observer but an active participant in the construction of knowledge (Kitcher, 1982; Rosenberg, 2000; Barber & Gracia, 1994).

In this grand tapestry of identity exploration, these philosophers offer diverse and often contrasting perspectives on the nature of the self. Each contributes to the rich mosaic of human self-understanding, reminding us that the question of identity is a profound and multifaceted inquiry that spans the ages.

Identity in the face of Industrialization and scientific progress

The XIXth century witnessed a profound reaction to the societal transformations brought about by the Industrial Revolution. In response to the dehumanizing effects of industrialization, Romanticism emerged as a cultural and intellectual movement that celebrated the unique individual experience. Philosophers and poets played pivotal roles in shaping this narrative.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a key figure in Romantic thought, challenged the prevailing social contract theories of his time by emphasizing the inherent goodness of individuals in their natural state. His focus on the authenticity of personal experience laid the groundwork for a more subjective understanding of identity (Scott, 2023). Subsequently, William Wordsworth’s poetic expressions, notably in works like “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey,” reflected a deep connection between the individual and nature (Wordsworth, 1798). This emphasis on subjective experience underscored a shift towards an inward exploration of identity in response to the external changes brought about by industrialization.

As the XIXth century progressed, existentialism emerged as a philosophical movement that delved into the nature of individual existence, freedom, and choice. First existentialist thinkers challenged traditional notions of identity and agency.

Thus, Seren Kierkegaard’s exploration of faith and individual choice laid the groundwork for existentialist thought. His concept of the “leap of faith” emphasized the individual’s subjective experience and the importance of personal commitment to shaping identity (Stokes, 2008; Matuštík, 1993). Friedrich Nietzsche, a vocal critic of traditional morality, questioned established values and championed the idea of the “Ubermensch” or “overman” (Nietzsche, 1885). His exploration of the individual’s capacity to transcend societal norms and create their values contributed to a reevaluation of identity in a more autonomous light (Davey, 1987).

On top of that, the scientific and technological progress of the XIXth century, marked by the increasing dominance of Newtonian physics and the rise of Darwinian evolutionary theory, provoked profound philosophical reflections on determinism and human nature. Many philosophers reacted against the deterministic worldview implied by Newtonian physics. The notion that the universe operated like a clockwork mechanism led to debates about the implications for human agency and identity. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution challenged prevailing views on the fixed and unchanging nature of humanity (Darwin & Kebler, 1859). The idea of adaptation and change over time raised questions about the stability and continuity of human identity within the larger context of evolutionary processes.

In response to the challenges posed by scientific determinism, the XXth century witnessed the emergence of phenomenology, a philosophical approach that shifted the focus from objective realities to the subjective experience of consciousness (Akhtar & Samuel, 1996). Edmund Husserl considered the founder of phenomenology, advocated for a method that emphasized the examination of consciousness and the structures of subjective experience. This shift laid the foundation for understanding identity not as a fixed entity but as a lived and evolving experience (Rasmussen, 1995; Jacobs, 2021).

The advent of phenomenology marked a turning point in philosophical discourse, redirecting attention towards the subjective dimensions of identity. This shift laid the groundwork for subsequent philosophical explorations of identity as a dynamic and personal phenomenon.

This transitional period set the stage for the reevaluation of identity in the context of the changing socio-cultural and technological landscape, providing a philosophical foundation for understanding the individual in the face of industrialization and scientific progress.

Contemporary perspectives on identity

Building upon the foundations laid by Immanuel Kant, contemporary philosophy offers a rich tapestry of perspectives on identity that transcends traditional frameworks. In the post-Kantian era, philosophers engage in diverse inquiries, challenging preconceived notions and reshaping our understanding of selfhood.

As for the poststructuralism and deconstruction era, Michel Foucault’s profound examination of power structures extends into the shaping of identities. His concept of the “panopticon” serves as a metaphor for the pervasive surveillance and disciplinary power embedded in society. Foucault challenges fixed notions of identity, spotlighting the fluid and dynamic nature of subjectivity (Foucault, 1977; Strozier, 2002). Jacques Derrida’s deconstructionist approach questions binary oppositions and hierarchical structures. By focusing on language and the concept of “differance,” Derrida destabilizes the stability of meaning and identity, introducing the idea that identity is a process rather than a fixed entity (Nealon, 1996).

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, building upon phenomenology, directs attention to the embodied nature of consciousness. His ideas emphasize the crucial role of the body in shaping our experiences and sense of self. The body, in Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy, transcends being merely a physical entity; it becomes a lived and experienced dimension of identity, intertwining subjectivity with corporeal existence (Antich, 2018; Muldoon, 1997).

Narrative identity’s perspective, influenced by thinkers like Paul Ricoeur and Daniel Dennett, posits that personal identity is constructed through the narrative we create about our lives (Dennett, 2017). The continuity and coherence of this narrative contribute to a sense of identity.

Some contemporary philosophers argue that personal identity is deeply intertwined with social context. The relationships and social roles one occupies contribute significantly to the formation of identity. The concept of the dialogical self inspired by the works of Mikhail Bakhtin, this perspective posits that the self is formed through internal dialogue and interaction with others (Clark & Holquist, 1984). The self is seen as a dynamic, evolving process rather than a fixed entity.

There are also reductionist theories. Physicalist views, influenced by materialism and functionalism, assert that personal identity is entirely grounded in physical processes, such as brain activity. From this perspective, the mind is reducible to the brain, and consciousness is a product of neurobiological processes. Prominent philosophers associated with physicalism include Paul Churchland (Churchland, 2013) and Jaegwon Kim (Kim, 2007). Philosophers like David Wiggins emphasize the role of biological continuity in personal identity (Wiggins, 2001). This includes the idea that the persistence of a particular organism or a set of biological features is crucial for maintaining identity.

Drawing on the advancements in neuroscience and cognitive science, German philosopher Thomas Metzinger’s exploration delves into the nature of self and consciousness. This work raises critical questions about the neural basis of identity, challenging traditional notions of a stable, enduring self. Metzinger’s interdisciplinary approach invites a reevaluation of the philosophical landscape by incorporating empirical insights from cognitive science (Metzinger, 2004; Blanke & Metzinger, 2009).

In the context of the technologically mediated world, Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” challenges conventional boundaries between humans and machines. Haraway explores how technology influences our identities and blurs distinctions between the natural and the artificial, the human and the non-human (Haraway, 1985; Mansfield, 2020). Biometrics emerges as a focal point, playing a pivotal role in redefining our understanding of identity by blending the organic and the technological.

Contemporary scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw’s introduction of intersectionality also important for understanding identity. This framework emphasizes the interconnected nature of social categories such as race, gender, and class (Crenshaw, 1989). It acknowledges the complexity of individuals’ identities, shaped by the intersections of various social factors. Identity becomes a multidimensional and evolving concept, reflecting the intricate interplay of diverse elements.

Indian-British scholar and critical theorist Homi K. Bhabha’s exploration of hybridity and the concept of the “third space” unfolds in the context of globalization (Bhabha, 2012). Bhabha challenges fixed notions of identity, suggesting that identities are in a constant state of negotiation and transformation. Cultural and individual identities are no longer confined within rigid boundaries but are, instead, dynamic and fluid, adapting to the complexities of a globalized world.

Within environmental philosophy, Arne Naess’s contribution to the concept of “deep ecology” extends the notion of identity beyond the anthropocentric realm (Naess, 1984). Norwegian philosopher’s perspective emphasizes the interconnectedness of all living beings, recognizing the inherent value of the natural world. In doing so, it broadens the understanding of identity to encompass the ecological fabric in which humanity is intricately woven.

In the present-day philosophical landscape, thinkers continue to navigate the complexities of identity in a rapidly changing world. These diverse perspectives, each offering a unique lens, collectively enrich our comprehension of identity as dynamic, context-dependent, and multifaceted.

Part II. Technological dimensions of biometrics: Orchestrating precision and innovation

‘The human face is, after all, nothing more nor less than a mask.’

– Agatha Christie

‘The serial number of a human specimen is the face, that accidental and unrepeatable combination of features. It reflects neither character nor soul, nor what we call the self. The face is only the serial number of a specimen’.

– Milan Kundera

Imagine a symphony, not of violins and cellos, but of fingerprints, retina scans, and the steady hum of algorithms. This is the world of biometrics, where biological identifiers dance in a complex choreography of precision and innovation. In this section, we explore the technological dimensions of biometrics, a realm where sensors and algorithms work together to safeguard our identities and unlock a new era of personalized security.

Biometric modalities: The canvas of identity

Biometrics is a multidimensional field situated at the intersection of technology, history, philosophy, and culture, offering a unique lens through which we perceive and authenticate identity. At its core, biometrics leverages distinctive modalities that encompass distinctive physiological or behavioral attributes, such as fingerprints, facial features, and vocal patterns. These features serve as unique identifiers, playing a pivotal role in authentication and access control systems (Bolle et al., 2013; Jain et al., 1996; Jain, et al., 2007).

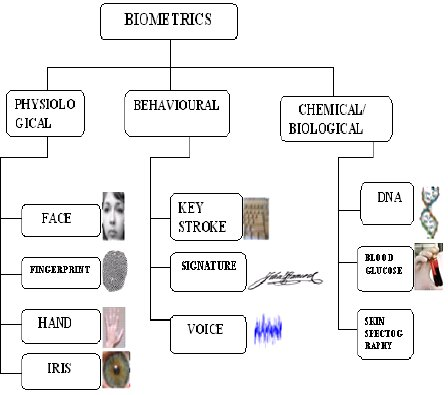

Biometric modalities can be categorized into three main classes. Physiological characteristics are linked to the body’s shape, with fingerprints being the oldest authentication system used for over a century. Other examples include face recognition, hand geometry, iris recognition, etc. Behavioral characteristics are associated with a person’s behavior. The signature, the first characteristic used and still widely employed today, is joined by more modern approaches such as keystroke dynamics and voice analysis. Chemical/Biological characteristics involve the chemical analysis of various biological parameters. This represents the latest frontier in biometric authentication systems, with examples including DNA structure analysis, blood glucose measurement, and skin spectrography.

Touch meets tech: Navigating the frontiers of biometric building blocks

The complex fabric of biometrics is intricately woven with advanced sensor technologies, sophisticated algorithmic processes, and secure storage mechanisms. This dynamic interplay of elements continuously reshapes the paradigm of identity verification, offering both increased security and convenience.

Thus, the foundation of biometrics lies in the sophisticated array of sensor technologies meticulously designed to capture the unique nuances of human physiology and behavior. Fingerprint scanners, employing capacitive or optical sensors, minutely analyze the ridges and valleys of fingerprints. Facial recognition cameras map facial features, discerning even subtle expressions. Iris scanners delve into the intricate patterns of the iris, while voice recognition microphones capture the distinctive cadence and tone of an individual’s voice. These sensors serve as the gatekeepers of identity, transforming biological traits into streams of digital data for further analysis (Oloyede & Hancke, 2016).

The magic of biometrics unfolds in the algorithmic realm, where raw biometric data undergoes a transformative journey. Machine learning algorithms dissect patterns, discerning the unique signatures embedded in fingerprints, facial features, or vocal modulations (Kung et al., 2005; Palaniappan & Mandic, 2007). AI, continuously learning and adapting, refines the accuracy of biometric templates, ensuring that the digital representation mirrors the subtleties of the individual (Kairinos, 2019; Jaswal et al., 2021; Abdullahi et al., 2022). Algorithmic advancements not only enhance accuracy but also contribute to the adaptability of biometric systems in diverse scenarios.

Biometric data, once captured, undergoes a metamorphosis into digital templates. These templates encapsulate the essence of an individual’s unique biometric markers and become the cornerstone of identity verification. Crafting templates that balance accuracy with resistance to tampering is a meticulous process. The challenge lies in maintaining the delicate equilibrium between creating a faithful representation of the individual and safeguarding their privacy through secure and encrypted storage mechanisms (Jain et al., 2005).

The sanctity of biometric data hinges on secure storage and encryption (Soutar et al., 1999; Cavoukian & Stoianov, 2007). Biometric databases, akin to digital vaults, employ robust encryption techniques to shield templates from unauthorized access. The emphasis is on protecting individual privacy while ensuring that, even in the event of a breach, the stored biometric data remains indecipherable and unusable. This dimension underscores the ethical responsibility inherent in managing sensitive personal information.

In an era where immediacy is paramount, many biometric systems operate in real-time, demanding swift processing capabilities. Whether authenticating a user for smartphone access or identifying individuals in a crowded space, real-time processing ensures efficiency and responsiveness. This dimension involves optimizing both hardware and software components to facilitate instantaneous decision-making, adding a temporal layer to the complexity of biometric technologies.

On top of that, biometrics thrives in synergy with other technologies, forming a comprehensive ecosystem of identity verification. Integration with access control systems, surveillance cameras, IoT, and mobile devices amplifies the effectiveness of biometrics across diverse applications. This collaborative approach highlights the adaptability of biometrics, seamlessly fitting into various contexts, from securing sensitive facilities to simplifying everyday tasks like device unlocking.

The technological dimensions of biometrics are not static but perpetually evolving. Continuous advancements drive the field forward, introducing novel technologies that push the boundaries of identity verification. Recent advancements including machine learning and AI have substantially improved accuracy and efficiency. These technologies have ushered in a new era of biometric systems capable of adapting to dynamic environmental conditions. From 3D facial recognition, offering enhanced accuracy, to advances in liveness detection (Nogueira et al., 2016), cancellable biometrics (Rathgeb & Uhl, 2011; Manisha, 2020), multimodal (Ross & Jain, 2004), multimodal behavioral biometrics (Bailey et al., 2014), the ongoing research and development in biometrics promise a future where innovation continues to shape secure and efficient identification systems.

Part III. Biometrics: Historical evolution

‘It is necessary to prepare the imminent and inevitable identification of man with the motor, facilitating and perfecting an incessant exchange of intuition, rhythm, instinct and metallic discipline…’

– Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Biometrics has a rich historical evolution that spans across cultures and centuries. The development of biometric identification methods can be traced through key milestones that have shaped its contemporary landscape.

In Part III, we embark on an exploration of biometrics’ historical evolution. We’ll unravel the threads from ancient civilizations and the anthropometry of the XIXth century to the sophisticated tech shaping our present. Witness the fingerprint’s rise to prominence, the iris’s captivating emergence, and the ever-expanding spectrum of biometric modalities transforming the way we verify identity.

Roots of biometrics

Ancient era

The roots of biometrics can be found in ancient civilizations, where rudimentary forms of identification were based on physical attributes (Li, 2009; Ashbourn, 2014). The Chinese, for example, used fingerprints as signatures on legal documents as early as 200 B.C. In ancient Babylon, individuals pressed their fingerprints into clay tablets for business transactions. Ancient Egyptians, meanwhile, employed facial recognition for purposes such as verifying identity during the mummification process.

The emergence of biometric principles finds its early roots in the cradle of civilization — Mesopotamia. Around 3500 BCE, Mesopotamians ingeniously employed cylinder seals crafted from stone or clay for the dual purposes of authentication and authorization. These cylindrical artifacts were not merely functional tools; rather, they were intricate pieces bearing unique engravings that functioned as identifiers akin to ancient fingerprints. The impressions left by these seals on clay tablets marked the advent of personal recognition and validation, offering a fascinating glimpse into the nascent stages of biometric authentication.

In the ancient realm of China, during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), an innovative approach to authentication surfaced through the use of handprints and fingerprints. The distinct ridges and patterns present on an individual’s fingers served as a distinctive mark, applied methodically on legal documents and contracts. This early recognition of the individuality embedded in biometric features demonstrated a remarkable understanding of the uniqueness inherent in human physiological traits, foreshadowing the future development of sophisticated biometric identification systems.

Within the meticulous record-keeping culture of ancient Egypt, facial features took center stage as a form of identification. Hieroglyphs and artistic representations on tombs and monuments depicted individuals with discernible facial attributes, establishing a form of facial recognition that transcended the practicalities of record-keeping. This artistic integration of facial features underscored the cultural importance of individual identity, reinforcing the notion that even in antiquity, the human face held significance as a unique marker.

The incorporation of biometric practices in ancient civilizations transcended mere functional necessity, unveiling profound cultural and philosophical dimensions. Beyond serving as tools for identity verification, these early biometric methods laid the groundwork for societal organization, reflecting humanity’s enduring fascination with individuality and uniqueness. The intricate interplay of cultural norms and practical necessities in ancient biometrics highlights the intrinsic human drive to establish order and recognize the distinctiveness of each individual within the collective fabric of society.

Renaissance and the emergence of signatures

As Europe transitioned from the medieval period to the Renaissance during the XIVth to the XVIIth centuries, a profound cultural, artistic, and intellectual transformation unfolded (Copenhaver, 1992). This period, marked by a revival of classical learning and the flourishing of the arts and sciences, also witnessed significant developments in the realm of personal identification.

One notable development during the Renaissance was the increasing use of signatures as a form of personal identification (Goffen, 2001; Matthew, 1998; Rubin, 2006). In contrast to the earlier reliance on physical attributes or artistic representations, individuals began to assert their identity through handwritten signatures. The act of signing one’s name became a distinctive mark, serving as a unique identifier and a symbol of personal responsibility.

The widespread use of signatures during the Renaissance aligned with broader societal shifts toward recognizing and affirming individual autonomy. The ability to sign one’s name became a symbol of literacy, education, and social standing, allowing individuals to assert their agency in various aspects of life.

The adoption of signatures had far-reaching legal and commercial implications, reshaping the landscape of contractual agreements and official documentation. As societies transitioned from oral traditions to written records, the personal signature emerged as a crucial element in validating the authenticity of documents. Legal instruments such as contracts, deeds, and treaties now require the personal mark of the involved parties for legitimacy. The uniqueness of each person’s handwriting added a layer of individuality and authenticity, fostering a standardized method of identification in legal and commercial transactions. This shift not only contributed to the establishment of a more secure and reliable authentication process but also laid the foundation for the modern legal significance of signatures in the documentation of agreements, emphasizing the enduring impact of this Renaissance development. In addition to their functional role in legal and commercial contexts, signatures during the Renaissance also took on an artistic dimension. Many individuals began to develop elaborate and stylized signatures, turning the act of signing into a form of personal expression. This artistic flourish not only added a touch of individuality but also reflected the cultural emphasis on personal identity and the unique qualities of each person.

The Renaissance’s influence on personal identification and authentication methods left an enduring legacy that transcended the boundaries of time. It is particularly evident in the modern era, where handwritten signatures have evolved into digital signatures and biometric authentication methods. They, however, proved susceptible to forgery, leading to the exploration of more reliable methods.

Early identity verification

The anthropometric era: Bertillon and precise measurements

In the late 19th century, as societal demands for accurate criminal identification grew, Alphonse Bertillon, a French police official and anthropologist, introduced a systematic method known as Bertillonage. Emerging in the era of forensic innovation, Bertillon sought to address the limitations of existing identification techniques. Bertillonage, developed in the 1880s, marked a significant shift in the scientific approach to criminal identification, emphasizing precision and standardization.

At the core of Bertillonage was a meticulous system that relied on a set of standardized measurements and descriptions of an individual’s physical features. Bertillon’s method included detailed measurements of the head, face, arms, and body, capturing specific anatomical details such as the length of fingers and ears (Bertillon, 1893; Ellenbogen, 2012). These measurements were compiled into a comprehensive identification record, creating a unique “anthropometric” profile for each individual. Alongside these measurements, Bertillonage incorporated detailed photographs and written descriptions of features such as scars, tattoos, and other distinctive marks. The resulting dossier aimed to provide law enforcement with a reliable and standardized means of identifying and cataloging individuals in a pre-fingerprint era.

Bertillonage gained swift recognition and adoption in law enforcement circles, both in France and internationally. Its standardized approach offered a systematic means of criminal identification that transcended the subjective nature of eyewitness accounts. Governments and police agencies embraced Bertillon’s system as a revolutionary step forward in the fight against crime. It was particularly instrumental in the identification of repeat offenders and the prevention of false identities.

Despite its initial success, Bertillonage faced criticisms, particularly as fingerprinting technology emerged as a more accurate and efficient alternative. Critics argued that Bertillon’s method, while groundbreaking, was labor-intensive, prone to human error, and lacked the precision of fingerprinting. The Bertillon system faced a significant decline in the early 20th century, ultimately being superseded by fingerprinting as the dominant method of criminal identification.

While Bertillonage may have fallen out of favor, its impact on forensic science and criminal identification was profound (Arbab‐Zavar et al., 2015). Alphonse Bertillon’s emphasis on standardization, systematic measurements, and detailed documentation laid the groundwork for the scientific methods that followed. The meticulous record-keeping and attention to detail in Bertillonage contributed to a broader understanding of the importance of objective and standardized approaches to criminal identification. While superseded by more advanced technologies, Bertillonage remains a historical milestone in the evolution of forensic science and the quest for accurate and reliable methods of personal identification.

Fingerprinting: Galton and the beginnings of modern biometrics

Sir Francis Galton, a 19th-century polymath and cousin of Charles Darwin, significantly contributed to the development of biometrics by focusing on fingerprints. Galton’s work laid the foundation for the scientific study of fingerprints and their uniqueness. The first systematic use of fingerprints in law enforcement occurred in British India in the late 19th century, and the methodology gained international recognition in the early 20th century (O’Gorman, 1996; Cole, 2004; Ellenbogen, 2012).

Sir Francis Galton’s key innovation was the development of a systematic classification system for fingerprints. Building upon earlier observations by individuals such as Marcello Malpighi and Johannes Purkinje, Galton conducted extensive research to establish the uniqueness and permanence of fingerprints. He categorized fingerprint patterns into arches, loops, and whorls, recognizing the distinctive features that set each individual’s prints apart. This classification system laid the groundwork for subsequent fingerprint identification methodologies and underscored the individualistic nature of fingerprints.

Galton’s fingerprint classification system gained practical significance when it was later implemented by Sir Edward Henry, a British police official, in the early 20th century. Henry’s adaptation of Galton’s method led to the establishment of the first systematic fingerprint identification system used by law enforcement (Berry & Stoney, 2001). Fingerprinting quickly proved to be a highly effective and reliable method, offering a level of precision and accuracy previously unmatched in the field of criminal identification.

The success of fingerprinting as an identification method led to its widespread acceptance in legal and law enforcement circles. Courts began to recognize the scientific reliability of fingerprints as evidence, solidifying the method’s legal standing. The application of fingerprints not only revolutionized criminal investigations but also influenced the development of forensic science as a whole, establishing a benchmark for the objective and systematic analysis of physical evidence.

Sir Francis Galton’s pioneering work laid the cornerstone for the global adoption of fingerprinting as the preeminent method of personal identification. The enduring legacy of his research is evident in the continued use of fingerprints in modern forensic practices and law enforcement. Fingerprinting has become an integral component of criminal investigations, border control, and civil identification worldwide, embodying Galton’s vision of a reliable and universal method for establishing individual identity. The birth of fingerprinting, guided by Galton’s scientific rigor, represents a transformative chapter in the history of forensic science and remains a testament to the enduring power of systematic and empirical approaches to personal identification.

World War II and biometrics

World War II catalyzed significant advancements in biometrics, driven by the strategic imperatives of the conflict. With the need for accurate identification of military personnel, prisoners of war, and civilians, governments and military forces turned to innovative biometric technologies to enhance security, streamline processes, and ensure the effectiveness of wartime operations.

During World War II, facial recognition technology gained prominence as a means of identifying individuals, particularly in military and intelligence applications. The war necessitated swift and accurate identification in diverse operational environments, prompting the development of facial recognition systems for both security and administrative purposes. Photographs and visual records became essential tools for cataloging and verifying the identities of military personnel and detainees.

The wartime period also witnessed notable advancements in fingerprinting technology. Fingerprint identification, which had gained traction in the early 20th century, saw further refinement and standardization during World War II. Military and law enforcement agencies increasingly relied on fingerprint databases for the identification of soldiers, spies, and individuals involved in wartime activities. These developments not only improved the efficiency of identification processes but also laid the groundwork for the post-war expansion of biometric technologies.

World War II marked the advent of voice recognition technology for communication security purposes. Military intelligence agencies explored the use of voiceprints — unique acoustic patterns in an individual’s voice — as a means of verifying the identity of radio operators and ensuring the security of confidential communications. This early experimentation with voice biometrics laid the foundation for subsequent developments in voice recognition technologies.

The advancements in biometrics spurred by World War II had a lasting impact on both military and civilian sectors. Post-war, the technology developed for wartime identification found applications in law enforcement, immigration control, and civil administration. The increased reliability and efficiency of biometric identification methods contributed to the broader acceptance of these technologies in various aspects of public and private life, shaping the trajectory of biometrics well into the post-war era and beyond. The wartime innovations in biometrics underscored the potential for these technologies to enhance security and streamline identification processes on a global scale.

Biometrics in the digital age

Computerization of biometrics

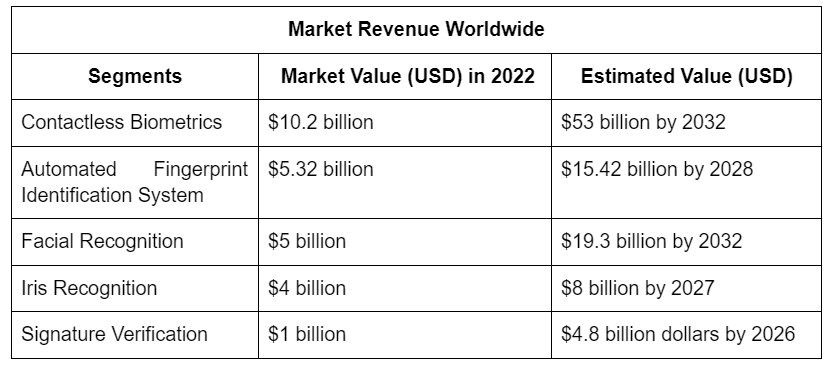

The advent of computers in the mid-20th century facilitated the digitization of biometric data. The development of automated fingerprint identification systems (AFIS) in the 1960s marked a significant leap forward, enabling faster and more accurate identification (Komarinski, 2017). Subsequent decades saw the integration of other biometric modalities, such as iris recognition, facial recognition, and voice recognition, and the creation of advents like liveness detection and multimodal biometrics into technological applications. Mainly, the digital age ushered in a paradigm shift in biometric identification, enabling unprecedented levels of accuracy, efficiency, and scalability (Wayman, 2007; Mordini & Massari, 2008).

- Big data

The digital age brought about the integration of biometric data into large-scale databases (Ratha et al., 2015). The ability to store and analyze vast amounts of biometric information, often referred to as “big data,” transformed the landscape of identity management. Governments, corporations, and organizations could now leverage sophisticated algorithms to process and interpret biometric data on a massive scale, leading to enhanced security and more effective identity verification processes.

- Blockchain

Blockchain technology is revolutionizing the field of biometrics, offering a robust solution to address challenges related to security and privacy (Hao, Anderson & Daugman, 2006; Delgado-Mohatar et al., 2020; Garcia, 2018). Leveraging blockchain’s decentralized and cryptographic features, biometric data, such as fingerprints and facial features, can be securely stored on a distributed ledger. This ensures enhanced security, as the decentralized nature of the blockchain eliminates the risks associated with a single point of failure, making it exceptionally difficult for malicious actors to compromise the integrity of biometric databases.

The immutability of blockchain contributes to the reliability of biometric records. Once recorded on the blockchain, biometric data becomes tamper-proof, providing a trustworthy and unalterable record of individuals’ unique characteristics. This not only safeguards against unauthorized alterations but also establishes a transparent and accountable system for managing identity information. Furthermore, blockchain’s user-centric approach empowers individuals to have greater control over their biometric data, allowing them to grant selective access and manage permissions as needed.

Interoperability is another key advantage of integrating blockchain into the biometrics landscape. Blockchain provides a standardized and secure platform for sharing and verifying biometric data across diverse applications and industries. This interoperability is particularly valuable in scenarios where different entities, such as government agencies, financial institutions, and healthcare providers, need access to a person’s identity information. Through the combination of blockchain and biometrics, the potential for reducing identity fraud, automating authentication processes with smart contracts, and fostering a more secure and transparent identity management system becomes increasingly evident.

Projects like Humanode pioneer a crypto-biometric L1 blockchain, employing proof of uniqueness and proof of existence for Sybil resistance (Kavazi et al., 2021). Worldcoin introduces a Proof of Personhood (PoP) system using iris scans, emphasizing privacy through zero-knowledge proofs. Governor DAO focuses on decentralized governance with biometrically verified proof-of-existence tokens, ensuring security through encrypted biometric information. Anima’s dID protocol utilizes biometric technology for PoP. These projects exemplify the transformative potential of biometrics in establishing secure identities, decentralized governance, and incentivizing widespread adoption in the digital age.

- Fingerprint recognition and automated systems

Computerization played a pivotal role in advancing fingerprint recognition systems. Automated fingerprint identification systems (AFIS) emerged, allowing for the rapid and accurate matching of fingerprint data against large databases (Komarinski, 2017). The digitization of fingerprint images not only expedited the identification process but also enhanced the reliability of biometric matching, making it an invaluable tool for law enforcement, border control, and forensic investigations.

- Advanced facial recognition

Facial recognition technology has undergone significant advancements, propelled by improvements in computer vision, artificial intelligence, and deep learning (Kaur at al., 2020). These advancements enable systems to recognize faces with greater accuracy, even under challenging conditions such as low light or varied facial expressions. Moreover, the incorporation of 3D facial recognition and anti-spoofing measures has enhanced security, making facial recognition a versatile and widely used biometric modality (Chang et al., 2003; Russ et al., 2004). Applications range from unlocking smartphones to surveillance and public safety initiatives, showcasing the adaptability and effectiveness of advanced facial recognition systems.

- Liveness detection

As biometric systems became more prevalent, the need to address potential vulnerabilities, such as spoofing or presentation attacks, led to the incorporation of liveness detection technologies. Liveness detection ensures that the biometric data being captured is from a living, present person rather than a static image or a replica (Nogueira et al., 2016; Marcialis et al., 2009; de Freitas Pereira et al., 2014). Computer algorithms were developed to analyze dynamic facial features, ensuring the authenticity of the biometric data being processed.

- Iris and retina scanning

Advancements in computer technology also facilitated the development of iris and retina scanning technologies (Nigam, Vatsa & Singh, 2015; Wildes, 1997). These highly accurate biometric methods leverage the unique patterns in the human eye for identification purposes. Computerized systems enabled quick and precise analysis of iris and retina images, making these modalities viable for applications requiring high levels of security, such as access to sensitive facilities and secure financial transactions.

- Voice biometrics

Voice biometrics, or speaker recognition, has become an increasingly sophisticated modality in the biometric landscape. Analyzing unique vocal characteristics such as pitch, tone, and speech patterns, voice biometrics offer a secure and user-friendly method of identification (Markowitz, 2000; Boles & Rad, 2017). With the rise of virtual assistants and voice-controlled devices, voice biometrics has gained traction in various industries, including banking, telecommunications, and customer service. Ongoing research aims to enhance the technology’s resistance to spoofing attempts and improve its accuracy in diverse linguistic environments.

- DNA biometrics

Advancements in molecular biology have led to the exploration of DNA as a biometric identifier (Jain & Kumar, 2010). DNA biometrics involves analyzing an individual’s unique genetic code for identification purposes. While still in the early stages of development, DNA biometrics hold great promise for forensic applications and high-security scenarios where the utmost accuracy is paramount. Ethical considerations and privacy concerns, however, accompany the use of DNA data, necessitating careful regulation and responsible implementation.

- Behavioral biometrics

The recognition that unique patterns exist in an individual’s behavior has led to the emergence of behavioral biometrics. This innovative approach analyzes distinctive traits such as keystroke dynamics, gait analysis, and signature dynamics to create a behavioral profile unique to each person. Behavioral biometrics offer a non-intrusive and continuous authentication method, as these patterns can be observed passively during regular activities. The integration of behavioral biometrics has proven valuable in scenarios where traditional biometric methods may be impractical, providing an additional layer of security for identity verification.

- Multimodal biometrics

The evolution of biometrics has seen a significant shift towards multimodal systems, which integrate multiple biometric modalities to enhance accuracy, reliability, and security (Ross & Jain, 2004). Rather than relying on a single identifier, such as fingerprints or facial features, multimodal biometrics leverage a combination of modalities, such as fingerprints, iris scans, and voice recognition, to create a more robust and comprehensive method of personal identification. This approach not only improves accuracy but also addresses challenges associated with unimodal systems, such as susceptibility to environmental factors or physical changes. Multimodal biometrics have found applications in high-security environments, border control, and identity management systems, offering a multi-layered approach to authentication.

- Continuous authentication

Traditional biometric systems often involve a one-time authentication process. However, the concept of continuous authentication has emerged to provide ongoing verification throughout a user’s session (Dahia et al., 2020). Behavioral biometrics, contextual analysis, and machine learning algorithms work together to assess the user’s identity continuously, adapting to changing conditions and potential security threats. Continuous authentication is particularly valuable in dynamic environments where persistent monitoring is essential for maintaining a secure user experience.

- Integration with wearable devices and the Internet of Things (IoT)

The merging of biometrics with wearable devices and the IoT represents a significant synergy, enhancing the functionalities of both technologies (Liang et al., 2020; Shah, 2016). Wearable devices, spanning from smartwatches to fitness trackers, now integrate biometric sensors for real-time analysis of physiological data, offering users immediate insights into their health and activities. This integration not only improves personalized experiences, enabling seamless identity authentication and health monitoring but also adds a sophisticated layer of security and personalization to the broader IoT landscape. As the IoT connects everyday objects, biometric data serves as a unique identifier, ensuring secure and tailored interactions within the interconnected network of devices. While streamlining user experiences, this integration prompts crucial considerations regarding privacy, data security, and ethical implications in an increasingly interconnected and sensor-rich environment.

Standardization and global acceptance

As biometric technologies gained prominence in the latter half of the XXth century, the need for standardization became increasingly apparent (Grother, 2008; Rane, 2014). With diverse applications across industries and countries, establishing common standards was crucial to ensure interoperability, reliability, and consistency in the deployment of biometric systems.

Recognizing the importance of standardization, international organizations played a pivotal role in developing guidelines and standards for biometric technologies. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) emerged as key entities leading standardization efforts. Their collaborative work resulted in the creation of standards that cover a wide range of biometric modalities, testing methodologies, and data interchange formats.

Beyond governmental and international initiatives, industry-specific standardization efforts emerged. For example, the Fast Identity Online (FIDO) Alliance introduced standards for online authentication, including biometric authentication methods. These industry standards further contributed to the widespread acceptance of biometrics in various sectors, from financial services to healthcare.

One crucial aspect of standardization focused on interoperability establishing common formats for the interchange of biometric data. Standards such as ANSI/NIST (American National Standards Institute/National Institute of Standards and Technology) for fingerprint data and ISO/IEC 19794 for general biometric data interchange paved the way for seamless communication and data sharing between different biometric systems and across international borders.

Global acceptance of biometrics relied heavily on the interoperability and integration of systems. Standardization efforts facilitated the development of biometric systems that could operate cohesively, allowing for the sharing of data and the integration of diverse biometric modalities. This interoperability was particularly crucial in applications such as international travel, law enforcement cooperation, and cross-border security initiatives.

To enhance the reliability and performance of biometric systems, certification and testing processes were developed by established standards. Certification programs ensured that biometric solutions met predetermined criteria for accuracy, security, and usability. This certification process became integral in assuring end-users and stakeholders of the quality and effectiveness of biometric implementations.

Standardization also played a role in the development of regulatory frameworks governing the use of biometrics. Many countries and regions adopted standardized approaches to ensure ethical practices, data protection, and privacy in the deployment of biometric technologies. Compliance with these standards became a benchmark for responsible and transparent use of biometric data, fostering public trust and acceptance (De Hert, 2005; Utegen & Rakhmetov, 2023).

Through the concerted efforts of international organizations, governments, industry stakeholders, and regulatory bodies, biometric standardization plays a pivotal role in achieving global acceptance. The establishment of common frameworks and the adherence to ethical principles and privacy considerations have contributed to the widespread integration of biometrics in diverse applications, from border control and law enforcement to financial transactions and consumer devices. Mass adoption, facilitated by the standardization of biometric tech has transformed these innovations from specialized tools to everyday features, making biometrics an integral part of modern identity management and security practices on a global scale.

Part IV. Biometrics: The philosophical landscape

‘Philosophy aims at teaching, as a whole and in general, the inner nature of things which expresses itself in these.’

– Arthur Schopenhauer

Biometrics is deeply intertwined with philosophical inquiries that probe the nature of identity, autonomy, and the ethical dimensions of surveillance. The philosophical underpinnings of biometrics give rise to a myriad of questions that extend beyond the technical aspects of the technology, prompting reflection on the fundamental values that underlie its deployment.

Philosophical underpinnings of biometrics

Biometric identity verification represents a modern dimension in the discourse on personal identity within philosophy. This aspect introduces the integration of advanced technologies and scientific methodologies to establish and authenticate an individual’s identity based on unique biological or behavioral characteristics (Jain et al., 2004; Jain & Kumar, 2010; Unar, Seng & Abbasi, 2014).

In recent years, considerable philosophical examination has been directed toward biometrics’ pertinent ethical and political considerations, particularly those stemming from issues of privacy, bias, and security in data collection (Lyons, 2008; Karkazis & Fishman, 2017). Additionally, scholars have delved into the metaphysical aspects raised by biometrics, with a specific focus on matters related to personal identity (van der Ploeg, 1999; Mordini, 2017; Mordini & Massari, 2008; Kind, 2023). In this part, we identify past thinkers and ideas that parallel and inform current understandings of biometrics.

- Identity, uniqueness, and the essential self

Exploring the realms of identity, individuality, and the core self, biometrics emerges as a profound philosophical subject. As societies progressively turn to biometric markers like fingerprints, iris patterns, or facial features for identification, deep questions arise regarding the philosophical understanding of personal uniqueness. What does it mean for an individual to be distinctly identified through these physiological traits? How does the reliance on biometrics reshape our perception of personal identity in the digital age?

Delving into the essence of identity from a philosophical perspective, the term “identity” functions as a descriptor — an intrinsic characteristic that distinguishes one entity from another. In this context, the focus is on emphasizing the unique qualities of the subject. Plato’s distinction between the copulative “is” in a phrase and the identifying “is” laid the groundwork for this concept (Gerson, 2004; Mates, 1979). Aristotle further nuanced the discussion by delineating identity in its numeric sense as equivalence and an identifier that individualizes an object.

Biometrics, relying on distinctive physical or behavioral traits, challenges traditional notions of identity that are detached from these measurable characteristics. This introduces a nuanced philosophical debate between essentialism and constructivism, highlighting the tension between inherent qualities and socially constructed identities. For example, the essentialist perspective, championed by philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, asserts that an individual’s identity is rooted in unchanging, inherent traits. Biometrics, in this light, aligns with the essentialist view by relying on immutable physiological features for identification. On the other hand, constructivist philosophers, such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, argue that identity is a product of experiences and societal influences (Locke, 1690; Curley, 1982; Stokes, 2008; Balibar, 2013). Biometrics challenges this perspective by emphasizing the role of physical characteristics as primary identifiers.

As society continues to adopt and adapt to biometric identity verification systems, the philosophical exploration of its implications becomes crucial. The intersection of technology and personal identity prompts reflections on the nature of selfhood, autonomy, and the evolving relationship between individuals and the increasingly sophisticated tools used to verify and validate their identities.

- Autonomy and informed consent

The ethical dimensions of biometrics (Mordini & Tzovaras, 2012) stretch into realms of autonomy and informed consent, sparking philosophical discussions about the genuine ability of individuals to provide meaningful consent in this era. In the age of biometrics, there is a growing debate on whether individuals can truly offer informed and voluntary consent to the collection and utilization of their biometric data. This raises fundamental questions about the voluntariness of participating in systems that often demand biometric identification.

From a philosophical standpoint, this presents a direct challenge to the concept of autonomy — the ability of individuals to make self-governed decisions. It also invites scrutiny of the importance of informed consent, drawing attention to whether individuals truly comprehend the implications of sharing their biometric information. To what extent should individuals retain agency over their biometric data, and how does the absence of genuine consent impact notions of personal freedom and self-determination?

The tension between security imperatives and the preservation of individual autonomy serves as a central theme in ethical analyses of biometrics. One example may be the work of Immanuel Kant, who emphasized the significance of individual autonomy in moral decision-making (Kitcher, 1982; Rosenberg, 2000; Barber & Gracia, 1994). In the context of biometrics, Kantian ethics would underscore the importance of respecting individuals’ capacity for rational decision-making and the need for transparent, informed consent.

Contrastingly, the utilitarian perspective, exemplified by philosophers like Jeremy Bentham, would weigh the overall societal benefits of biometric security against potential encroachments on individual autonomy (Bentham, 1843). This utilitarian calculus raises pertinent ethical questions about the greater good versus individual liberties in the context of biometric data usage.

- Surveillance and the panopticon

The philosophical exploration of surveillance and its societal implications has been a longstanding endeavor. The integration of biometrics into surveillance systems invokes parallels with Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon — a conceptual architectural design wherein individuals are subjected to constant observation (Bentham, 1843). This integration prompts profound considerations about power dynamics within the realms of those who engage in monitoring and those subject to constant surveillance. Insights from Michel Foucault’s analyses, specifically his examination of the disciplinary and normalizing effects of surveillance, gain prominence in discussions around the delicate equilibrium between societal safety and individual freedom (Foucault, 1977; Strozier, 2002). The normalization of behavior through continuous observation, a concept Foucault termed “panopticism,” comes into focus. The idea that individuals alter their behavior when aware of being watched aligns with concerns about the potential societal impacts of widespread biometric surveillance. The nuanced interplay between individual agency, societal norms, and the coercive power of constant observation underscores the complex ethical terrain of biometric surveillance.

Moreover, discussions surrounding biometrics and the panopticon resonate with contemporary debates on privacy, civil liberties, and the evolving nature of state power. The ethical implications of leveraging biometrics for surveillance draw attention to the need for safeguards that strike a delicate balance between maintaining societal safety and respecting individual autonomy.

- Ethics of data ownership and control

The ethical dimensions encompassing biometrics delve deeply into the realms of data ownership and control, prompting profound philosophical inquiries into the custodianship of biometric data, its storage modalities, and the entities with access to it. These deliberations intricately intertwine with broader philosophical debates on privacy and individual rights, elevating the discourse to a level that contemplates the very nature of data as a form of property. Such considerations become pivotal in scrutinizing matters of distributive justice, power differentials, and the latent potential for exploitation.

From a philosophical standpoint, the concept of data ownership evokes reflections on John Locke’s theories of property. Locke’s assertion that individuals have a natural right to own property under their labor finds resonance in the realm of biometrics (Locke, 1690; Curley, 1982; Stokes, 2008; Balibar, 2013). The labor involved in generating and providing biometric data raises questions about the rightful ownership of this unique and personal information.

Furthermore, the writings of Immanuel Kant contribute to the philosophical discourse on data control. Kant’s emphasis on individual autonomy and the categorical imperative underscores the ethical responsibility associated with the control and utilization of personal data (Kitcher, 1982; Rosenberg, 2000; Barber & Gracia, 1994). Applying Kantian principles to biometrics prompts contemplation on the ethical obligations of entities entrusted with managing this sensitive information.

Distributive justice, as elucidated by philosophers like John Rawls, becomes a pertinent lens through which to evaluate the ethical implications of biometric data ownership (Nagel, 1973; Pogge, 1989). Rawlsian principles of justice call for the fair distribution of societal goods, and the question arises: How can the ownership and control of biometric data be organized in a way that aligns with principles of fairness and equitable access?

- Ontological implications of digital identities

The integration of biometrics into the digitization of identity brings forth ontological inquiries, sparking philosophical reflections on the nature of existence in a digital realm. As individuals become encapsulated by algorithms and datasets, profound questions arise about the authenticity and integrity of a digital identity in comparison to its physical counterpart. This ontological shift prompts extensive contemplation on the nature of selfhood within an evolving landscape, marked by increasing digitization and interconnectivity.

From a philosophical perspective, the exploration of digitized identities may draw inspiration from Martin Heidegger’s ontological inquiries. Heidegger’s emphasis on “Being” and the essence of existence invites a nuanced examination of the digital realm’s impact on the very nature of human beings (Steiner, 1991). Questions arise about the authentic experience of selfhood when mediated through digital representations and the implications for one’s sense of existence.

Furthermore, Jean Baudrillard’s concepts of simulacra and hyperreality provide a framework for examining the authenticity of digitized identities (Baudrillard, 1994). Baudrillard’s contention that the digital realm often operates in a state of hyperreality, where representations become detached from the original, prompts considerations about the genuine nature of identities shaped and molded within digital spaces.

The integration of biometrics into the digitization of identity also aligns with the postmodern perspectives of thinkers like Jacques Derrida. Derrida’s deconstructionist approach invites an analysis of the inherent instabilities and fluidities in digital identities, challenging traditional notions of fixed and stable selfhood (Derrida, 2020).

- Existential dimensions

The integration of biometrics into our societal fabric injects profound existential dimensions into philosophical discussions. The dependence on biometric markers for identification propels inquiries into the very essence of existence, contemplating the existential implications of reducing an individual to a mere collection of measurable characteristics. This transformative shift prompts a philosophical exploration into questions surrounding the existential experience of being recognized — or potentially misrecognized — by technology, challenging established notions of human existence and the intersubjective nature of identity.

Existentialist philosophy, particularly the works of Jean-Paul Sartre, becomes a valuable lens through which to examine the impact of biometrics on the human experience. Sartre’s emphasis on radical freedom and personal responsibility (Sartre, 1946) invites reflection on how the reliance on biometric markers may influence individuals’ perception of their agency and autonomy. The existential angst of being objectified through biometric data raises questions about the authentic experience of selfhood in a technologically mediated world.

Albert Camus’ philosophy of the absurd also contributes to the discourse, inviting contemplation on the absurdity inherent in reducing the complexity of human existence to a set of measurable traits (Camus, 1942). The deployment of biometrics, with its reductionist approach to identity, echoes Camus’ exploration of the absurdity of human endeavors that seek meaning in a seemingly indifferent universe.

The phenomenological insights of Maurice Merleau-Ponty offer another perspective, emphasizing the embodied nature of human existence (Antich, 2018; Muldoon, 1997). In the context of biometrics, the lived experience of being recognized through one’s physical or behavioral traits becomes central, challenging the traditional mind-body dualism and inviting exploration into the existential significance of bodily presence in a technologically mediated reality.

- Privacy dilemmas

The collection, storage, and use of biometric data give rise to significant and nuanced privacy dilemmas, prompting a philosophical reflection on the intricate balance between heightened security measures and the fundamental right to protect personal information. Negotiating this delicate boundary becomes a focal point for ethical considerations, necessitating a thoughtful examination of the implications on civil liberties.

Philosophically, this privacy dilemma can be viewed through the lens of John Stuart Mill’s harm principle (Mill, 2022). Mill’s assertion that individuals should be free to act as they please unless their actions cause harm to others raises questions about the potential harm arising from the gathering and utilization of biometric data. This perspective invites an evaluation of whether the benefits of enhanced security justify the potential infringements on individual privacy.

Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative adds another layer to the discussion. Kantian ethics emphasizes treating individuals as ends in themselves rather than as means to an end (Kant, 1797). Applying this principle to biometric surveillance raises questions about whether the collection and use of personal data respect the autonomy and dignity of each individual, or whether they instrumentalize people for broader societal goals.